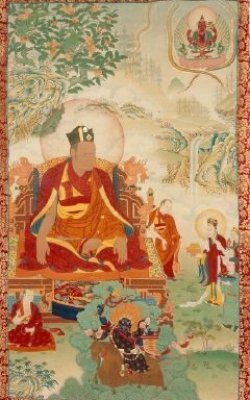

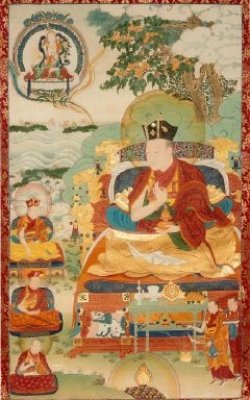

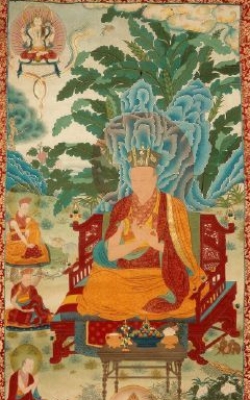

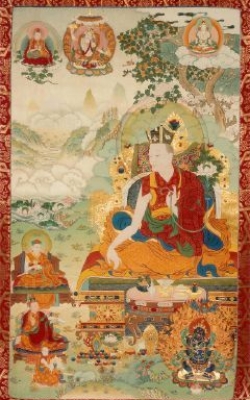

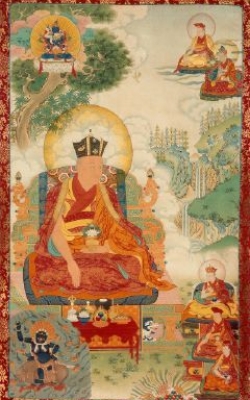

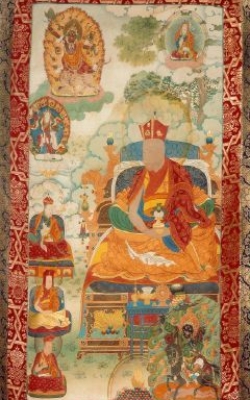

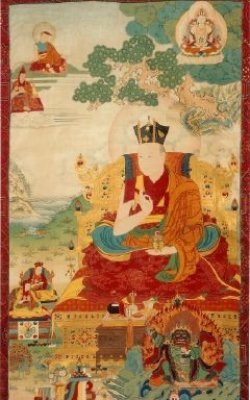

Karmapa II - Karma Pakshi

THE IInd KARMAPA

(1204 - 1283)

The second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi, was born in 1206 C.E. into a family descended from the eighth-century dharma-king, Trisong Detsun. His parents, who were devout religious practitioners, named their son Chödzin.

Chödzin was a precocious child and by the age of six he could read and write perfectly. By the time he was ten years old he had already grasped the essence of Buddhist doctrine. In addition to his intellectual ability, Chödzin also possessed an intuitive aptitude to rest the mind in stillness. As a result of this natural facility, when his meditation teacher, Pomdrakpa, introduced him to the nature of his own mind, he was able to develop spontaneous insight.

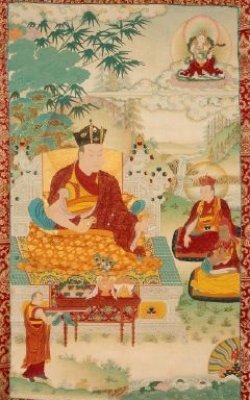

Pomdrakpa had himself received the teachings of the Karma Kagyu lineage from Drogön Rechen, the heir to Dusum Khyenpa's transmission. When he first bestowed an empowerment on Chödzin, he explained that in a vision he had seen Dusum Khyenpa and other teachers of the lineage surrounding his young student's residence, illustrating the latter's importance. In a further vision, Dusum Khyenpa revealed to Pomdrakpa that Chödzin was in fact his incarnation. From this time on, Pomdrakpa recognized Chödzin as the second Karmapa Lama and entitled him dharma master (Tib.: ཆོས་ཀྱི་བླ་མ།). In addition, he ordained Karma Pakshi as a novice.

For eleven years Karma Pakshi studied with Pomdrakpa, specializing in the mahāmudrā teachings of Saraha and Gampopa. With his natural ability he was able to accomplish the teachings as quickly as he received them. At the conclusion of this period of study Pomdrakpa told him that he had developed his own understanding sufficiently but that he also needed to have a lineage of empowerments, textual transmissions and instructions from Sākyamuni or Vajradhara to teach others. He gave Karma Pakshi the complete series of Kagyu teachings, and thus became his spiritual father. When Karma Pakshi received the empowerment of Mahākāla he experienced the actual presence of the dharmapāla.

At the age of twenty-two Karma Pakshi was ordained a monk by Lama Jampa Bum, abbot of the Katok Nyingmapa monastery, established by Kadampa Desheg, the student of the first Karmapa. In his own spiritual practice at this time, Karma Pakshi concentrated upon "inner heat yoga" combined with mahāmudrā itself. In this way he developed both the form and formless aspects of tantric practice.

This was a period of civil disturbances in Kham and Karma Pakshi responded to the needs of the people by touring the area in an attempt to bring about peace. The whole area with its fields, mountains and valleys appeared to him as an environment of complete happiness (Tib.: bde. mchog) which contained the potential for the spread of dharma. This was symbolized in his vision of Mahāsukha Cakrasamvara surrounded by the dance of dākas and dākinis. Later, inspired by the Vajra Black-Cloaked Mahākāla (Tib.: rdo.rje. ber.nag.can), who subsequently became the main dharma protector of the Karma Kagyu lineage, Karma Pakshi built a new monastery in the area of Sharchok Pungri in Kham.

In another vision, Karma Pakshi was instructed by a dākini to develop communal singing of the six-syllable mantra of Avalokiteshvara, embodiment of enlightened compassion. Karma Pakshi and his monks chanted the mantra as they traveled. From this time onward communal singing of the six-syllable mantra became an important part of popular religious practice in Tibet.

Karma Pakshi stayed at his new monastery for eleven years, engaged in intensive meditation practice. The fame of his spiritual power reached as far as Jang and China. Through his mastery of the energy of the four elements, Karma Pakshi pacified his environment. This was confirmed by the symbolic commitment of the mountain deity, Dorje Paltseg, to protect the Karma Kagyu lineage.

Subsequently, Karma Pakshi visited Karma Gon monastery, which had fallen into a state of disrepair. He restored it to its former condition. Then, inspired by Mahākāli, Karma Pakshi journeyed to Tsurphu and again carried out restoration work. Six years later, he went to the Tsang area of western Tibet via Lake Namtsho, where he obtained treasure which was used for the debts incurred during the restoration of the monastery.

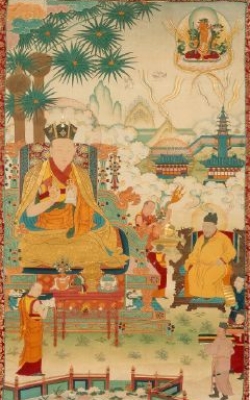

In 1251 Karma Pakshi received an invitation from Prince Kublai who at that time ruled the Sino-Tibetan border regions. In response, Karma Pakshi traveled to the Wu-tok palace, reaching there in the year 1254, after being welcomed by a large army at Serta on the way. Karma Pakshi was aware of the importance of his visit for the future of Kagyupa teachings and had many visionary experiences indicating this after his arrival at the court. He was honored by Kublai Khan, who requested him to display his spiritual power to the other religious teachers. Karma Pakshi complied with this request and also conducted himself with such courtesy that all acknowledged his greatness.

The khan asked him to remain at his court permanently, but Karma Pakshi declined, forseeing the potential for trouble in the factional interests at the court.

At this time, the rest of China was under the control of Mongka Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, who had deposed his own cousin, Godin. Mongka Khan exercised a rather tenuous control of his younger brother Kublai. During this period the Sakyapa school had spread its teachings throughout China, due largely to the work of Sakya Pandita (1182-1251) and his nephew, Phakpa (1235-1284).

Inspired by Avalokiteshvara and Mahākāla, Karma Pakshi decided to travel to northern Tibet.

Despite Kublai Khan's anger at his refusal to stay, he journeyed to the Sino-Tibetan border region of Minyak. When he arrived, the country was rocked by a tornado, which Karma Pakshi envisaged as the manifestation of the Vajra Black-Cloaked Mahākāla. He also had a vision of Vai'ravaqa, protector of wealth, who requested him to remain in Minyak in order to construct a new temple there.

By 1256 Karma Pakshi had reached Amdo in northeastern Tibet, where he learned that Mongka Khan had suppressed the power of his younger brother, Kublai, and was now the supreme ruler of Mongolia and a large part of China. At this point, Mongka Khan invited him to return to China to teach dharma. The invitation was accepted and Karma Pakshi traveled slowly back to China, passing through the Minyak region once again. In a visionary experience, he was inspired by the red Tārā to go to Mongka Khan's palace in Liang Chou. By this time the far-ranging importance of Karma Pakshi's dharma activity had become very clear. On the journey to Mongka Khan's court he removed both environmental and social imbalances by his compassionate activity.

Karma Pakshi arrived at the court at the beginning of the winter. The khan marked his arrival by freeing prisoners in his honor and Karma Pakshi manifested the enlightened compassion of Avalokiteshvara by giving many empowerments, textual transmissions and instructions.

The khan became his devoted student and Karma Pakshi revealed that he had in fact studied with the first Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa, in his previous life, and indeed had achieved the same mahāmudrā realization as Karma Pakshi himself. In order to display the superb skillful means of the dharma, Karma Pakshi invited many jealous Taoist masters from Shen Shing, Tao Shi, and Er Kao to join him in debate. However, none were equal to it and they all accepted his teaching.

At the Alaka palace, Karma Pakshi empowered the khan and his other students in the spiritual practice of Chakrasamvara. Mongka Khan practiced his instruction so precisely that he was able to visualize the yidam in perfect detail. Later, through the power of Karma Pakshi's meditation, a vision of Saraha and the other eighty-four tantric saints appeared in the sky, where they remained for three days. The power of his teaching cut through the khan's involvement with politics, enabling him to develop an intuitive realization of mahāmudrā.

Karma Pakshi's influence extended far beyond the royal court and indeed had a profound effect on Sino-Mongol culture. He continued the process begun by Sakya Pandita. As an example of this, Karma Pakshi advised that all Mongol Buddhists should avoid meat-eating on the days of the moon's phases. Similarly, non-Buddhists were advised to keep their own religious precepts on these days. The ten virtues enunciated by Sākyamuni Buddha were emphasized as the basis of individual and social morality. Karma Pakshi's work for the welfare of the people was very extensive. For example, on thirteen separate occasions groups of prisoners freed from confinement on his urging.

Despite his own personal prestige, Karma Pakshi did not seek to advance the Karma Kagyu school at the expense of the other Buddhist traditions, but urged the khan to support them as well. Subsequently the khan invited his guru to accompany him on a tour of his empire. At Karakorum, the Mongol's capital city, Karma Pakshi entered a friendly dialogue with the representatives of other religious traditions. The party traveled on to the Sino-Mongolian border regions and then journeyed to Minyak. Here, inspired by the memory of Dusum Khyenpa, Karma Pakshi decided to return to Tibet. Mongka Khan had wanted his guru to accompany him to Manchuria, but Karma Pakshi declined, pointing to the impermanent nature of all situations. The khan did not attempt to detain him but granted him a safe conduct pass through all Mongol territories.

However, in the year of the Iron Tiger, as Karma Pakshi returned to Tibet, trouble broke out in China upon the death of Mongka Khan. At first himself, Alapaga, the late khan's son, established his rule in spite of the fact that some Mongol chiefs supported the rival claim of his uncle, Kublai Khan. Soon, however, Kublai Khan was able to seize control and Alapaga was killed, reputedly by the magical power of a student of Lama Zhang of the Tsalpa Kagyu lineage.

At this time Karma Pakshi, whose journey had been delayed by local warfare, was inspired by a vision to construct a large statue of the Buddha, on his return to Tibet. However, he was acutely aware of the difficulties in the way of such a project. The way through these obstructions was revealed to him in a dream of a white horse, which rescued him from danger. He composed a song to celebrate this in which he declared, "This supreme horse is like a golden bird. I, myself, am the supreme man, as was Siddhārtha Gautama. Therefore, we will cross over these dangerous times." Word reached Karma Pakshi that Kublai Khan, encouraged by court intrigue, had developed a grudge against him. The khan felt that he had been slighted by Karma Pakshi and that the latter had encouraged his rival and brother, Mongka Khan, so he decided to order his assassination.

The new khan's soldiers detained Karma Pakshi and subjected him to various indignities and tortures such as burning, poisoning and being thrown off a cliff, but in the face of this brutal treatment he manifested the Avalokiteshvara and the natural freedom of a mahāsiddha.

Karma Pakshi's realization of the unborn and undying nature of mind meant that his captors were unable to harm him. Eventually he expressed great pity for their confusion. These events forced Kublai Khan to reconsider his attitude to Karma Pakshi. Instead of assassination, exile seemed appropriate. The khan attempted to damage Karma Pakshi's health by sending him to a deserted area near the ocean where there were few people to receive the dharma. However, within the next few years Karma Pakshi spent his time composing texts and slowly recovered. Eventually Kublai Khan relented and apologized, asking Karma Pakshi to stay with him. When Karma Pakshi replied that he had to return to Tibet, the khan allowed him to depart saying, "Please remember me and pray for me and bless me. You are free to go and teach dharma wherever you wish."

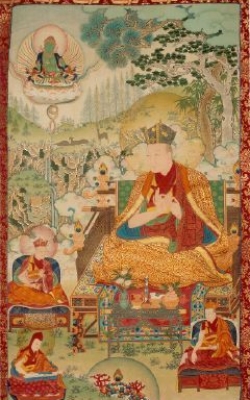

Karma Pakshi arrived back at Tsurphu after a long journey and set to work constructing the statue of Buddha. The cast brass statue, named "Great Sage, Ornament of the World" stood fifty-five feet tall and contained relics of the Buddha and his disciples. On completion the statue appeared to tilt to one side. Seeing this, Karma Pakshi entered into meditation, tilting his body in the same way. As he straigthened up, the statue righted itself.

Before his death in 1283, Karma Pakshi transmitted his lineage to his great student, Urgyenpa. He informed Urgyenpa that his next incarnation would come from western Tibet.

Karma Pakshi was both a profound tantric saint and scholar. The energy of his teachings inspired many people to travel the spiritual path. In addition to Urgyenpa, his other famous students included Maja Changchub Tsondru, Nyenre Gendun Bum and Mongka Khan.

Reproduced with permission of the Very Venerable Karma Thrinley Rinpoche