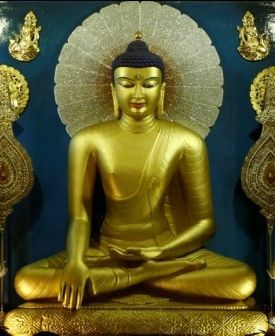

Statue of the Buddha

Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh-Gaya

As the first of the Three Jewels - (Tib. 'Konchog Sum' - Skt. 'Triratna' or the three Sources of Refuge, the term BUDDHA is a Sanskrit word referring to someone who has awaken from the gloom of ignorance and thus abandoned the production of non-virtuous acts , which cause suffering while having also perfected the generation of all virtue and merit as the root of long lasting happiness. This meaning is reflected in the tibetan expression 'sang-gyay' as follows:

The fruition of the Dharma path is to become sang gyay - a buddha - an Enlightened One. The Tibetan term was coined by the early Tibetan translators to render the meaning of the original Sanskrit term rather than as a literal translation:

A Buddha has become both 'sang pa' - woken up and 'gyay pa' - expanded.

- 'sang' means woken up in the sense that the obscurations have been purified completely.

- 'gyay' means expanded in the sense that all good qualities have been developed to their limit.

The Twelve Deeds of the Buddha

The following teaching is a compilation of a teaching given by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche, together with additional material on the subject, printed in italic.

Because of his immeasurable compassion toward all sentient beings, every Buddha shows these twelve deeds. He has complete omniscience and by his all-encompassing wisdom, he is able to recognize all phenomena in the different realms. With this wisdom of omniscience he performs the twelve deeds described hereafter. “The historical Buddha was an emanation of the Buddha mind, referred to here as a supreme nirmanakaya, i.e. most perfect emanated form. Such emanations manifest, even to worldly beings, as having the thirty-two major marks and eighty signs of perfection of an Enlightened Being, teaching Dharma in order to set the world into a cycle of wisdom and goodness. According to the Good Aeon Sutra, 1,002 such Buddhas have come and will come throughout the lifetime of this world, to awaken it over and over again to the timeless universal truths. Sakyamuni was but the fourth of these. Maitreya, the ‘Loving One', will be the fifth, and the being who is known in these times as the Gyalwa Karmapa will be the sixth, the ‘Lion Buddha'.

The various major events of Sakyamuni's life, such as his family background, his asceticism, etc., were not simple accidents but the meaningful and perfect conclusion to a very long and special story. In Mahayana Buddhism, it is considered that, from the time he first uttered the Bodhisattva vow, the Bodhisattva who was to become Sakyamuni Buddha took many hundreds of lifetimes to reach ultimate perfection. Altogether, these incarnations of systematic purification and steady development along the bodhisattva path spanned three cosmic aeons (a cosmic aeon, in this case, is the time from the inception of a solar system, such as our own, until its final destruction). After this extraordinary length of time, in which three universes had come and gone, he had purified absolutely everything in his being that there was to purify and he had attained every quality that a human being can attain. He achieved his final enlightenment in the ‘Highest' deva realm, called Akanistha, in Sanskrit, and Og-min in Tibetan. From there, he emanated into all the human realms of the thousand million cosmic systems with which he was associated. His ‘lives' in those realms, such as the one he led in India some 2,500 years ago, were a very meaningful yet spontaneous drama, enacted to make the Dharma teachings he imparted have the finest and most enduring effect on the world.

Such a vision of the purposefulness of the Buddha's life gives a very different image of him than that of a simple prince, at first influenced by Hinduism, who gradually became disillusioned with the royal life and one day set out into the unknown on a spiritual quest. His wisdom and perfection were there from the start, as bore witness the special signs on his body and the golden aura which shone for almost a kilometre around him as a child. The twelve major activities of his life, and their significance, are given in the following verses.”

There are very many great deeds of the Buddha recorded but these can be summarized into the twelve most important, most famous deeds.

First Deed: Descending from Tushita

When the Buddha was teaching in the paradise of Tushita, which is a realm where the devas (gods) reside and also a sambhogakaya realm, the sound of his previous motivation reminded him that it was necessary to take birth in our world and teach the Dharma.

He then considered five things:

- Right place: the land where he ought to be born (which was Kapila in Nepal);

- Right caste: the caste he should be born into which was a royal caste (The previous Buddha Kasyapa had found it more advantageous to be born into the priestly caste, as it was more prestigious in that age);

- Right family: the family in which he should be born, the Shakya clan made of all his former disciples was gathering in India. These would be beings capable of receiving and perpetuating his teaching.

- Right mother: the Queen Mayadevi, Queen Mahamaya, capable of bearing such an extraordinary child;

- Right time: and the time that was right for him to be born (which happened to be when the five degenerations were on the increase, the present time). After having made these determinations, he decided to leave the Tushita paradise and take birth in our world. This particular deed of leaving Tushita to be born had a special significance. It was intended to teach us that somebody who has achieved enlightenment is no longer a slave of his own karma and has control over anything he or she does. So the Buddha chose to take birth in our world because the time was right and he wanted to show us that someone who is enlightened has control over anything he or she does.

This is the dharmakaya's compassionate response to the hopes and prayers of good beings in the world. It is the arrival of the great light which illuminates the path to happiness and liberation, which shows the value of virtue and which accomplishes its work with a limitless love and totally fearless resolution.

![]()

Second Deed: Conception in the Womb

The Buddha was conceived in the womb of his mother, Mayadevi (by taking the form of a White Elephant descending from Tushita and entering the womb immaculately). One may wonder why he was conceived and then took birth. If he had complete control over everything, then why wasn’t he born miraculously from a lotus flower as was Padmasambhava or why couldn’t he simply descend from the sky?

The Buddha had a special reason for being born the normal way. If he had been born miraculously from a lotus, for example, it would have been very impressive and attracted many people. However, the Buddha was thinking in the long term of his future disciples who would be inspired because the Buddha, who practiced and achieved enlightenment, started out like ourselves. Had he been born in a lotus they would have thought no ordinary human beings could reach enlightenment because they didn’t have these same miraculous powers. So the Buddha entered the womb, he was conceived, to show that even ordinary human beings can achieve the highest realization. He did this to instil conviction and confidence in his future disciples.

His teachings of Dharma would later point out the limitations of worldly wealth, status and achievement. It would be very necessary that these worldly goals be removed from their pedestal and given their proper place by someone who had known them to the full. The words of a social failure, denouncing gain and fame, may just be dismissed as ‘sour grapes', as personal rancour. His future father, King Shuddhodana, was a respected and wealthy monarch. His mother, Mahamaya, was a beautiful queen, capable of bearing him. Therefore, he entered the royal womb. His mother dreamed of a white, six-tusked elephant entering her womb, as though it were a beautiful palace. There was celestial music and many other miraculous signs.

![]()

Third Deed: Birth in the garden of Lumbini

Although the Buddha took an ordinary human birth, there was still something very special in his birth. The Buddha came out of the body of his mother through her right side. Some people might wonder how this was possible. They might think, “Well, what exactly happened? Did the rib cage crack?” One doesn’t need to think in terms of anatomical problems because the Buddha was a miraculous being and he just took birth through his mother’s right side without any pain or obstacle. At the time of the Buddha’s birth, there were many very special things happening where he was born. All of a sudden, crops started growing. Trees appeared all over the area of Lumbini and rare flowers such as the Udumbara flower, that had never grown in this area, started blooming everywhere. Due to these events, from that moment onwards, he was given the name Siddhartha in Sanskrit, or Tungye Drup in Tibetan, which means, “the one that makes everything possible.” As a result of interdependent origination, the presence of a highly accomplished individual produces changes in the environment such as the blossoming of flowers (as in the case of the Buddha right after his birth).

To those present, he was seen simply to emerge on a beam of light. When his feet touched the ground, lotus flowers of light sprung up. He took seven steps in each of the cardinal directions and ‘was heard to declare' (i.e. everyone knew spontaneously) himself to be the Enlightened One, Lord of the World. The major gods of the planet came and prostrated before him. However, of equal importance with these miracles was the fact that, to most other people, he was later thought of as having been born ‘ordinarily' as a human being. This was crucial for his teaching. People would think that an ordinary human being like themselves, and not a celestial one, had achieved enlightenment and that they could therefore do likewise.

![]()

Fourth Deed: Training in the Arts, Crafts and Sciences

A few years later when the Buddha had grown up a little, he was educated and thus became very knowledgeable, very scholarly, and very skilful. This may be a little surprising, because the Buddha was already enlightened or at least a great Bodhisattva residing in the tenth Bodhisattva level (bhumi; there are ten stages to a Bodhisattva’s development, the tenth being the final stage before Buddhahood). People might think it should not have been necessary for him to train in worldly skills because he should have known them naturally. However, there was again a specific reason for doing this. It was to counteract various misconceptions we might have had. One misunderstanding was to think that the Buddha was someone who was simply a meditator without any academic education. Another misconception was the idea that he already possessed all this knowledge so he didn’t need to learn. This could give rise to concerns that if we humans tried to learn something it would lead to no results. Or again people might think that the Buddha did not have any qualities and that he never had to train. So to overcome these misconceptions the Buddha worked at becoming a scholar and became very skilled in all different arts. It also shows that it is necessary to receive full education in the culture in which we are born. We must therefore be part of the various positive aspects of our culture and then become a vehicle for transmitting the Dharma.

As he grew up, he exhibited matchless prowess in every field of learning. His beautiful athletic body surpassed all others in sports such as wrestling, archery and so on. He mastered sixty different dialects and soon outclassed his teachers in the various domains of academic study and artistic expression. As we see so clearly these days, people can value highly—perhaps overvalue—scientific understanding, art or physical prowess. In order for the Buddha's teaching to show the transience and limitations of such worldly prowess, compared with the true science of mind and existence itself, it was indeed helpful that he had known them and excelled in each of them more than anyone of his day. It is said that his fame as an athlete and scholar spread far beyond his own kingdom. He was a legend long before his enlightenment: the wisest, most gifted youth that humankind had ever seen.

![]()

Fifth Deed: Marriage to Yashodhara, the birth of his son Rahula and the enjoyment of royalty

The Buddha did this so that his future disciples wouldn’t think that the Buddha or an enlightened person was unable to enjoy any pleasures or feel the need for enjoyment. The other reason for the Buddha living such a sensuous life was to show that even though the Buddha had all the finest pleasures, he wasn’t satisfied by these pleasures because he understood that there was a higher form of happiness to be sought.

In order to fulfil his duty to his parents and provide an heir to the throne (he was their only child), he married and enjoyed the company of his royal consorts. The quest for a happy marriage, sexual satisfaction, parenthood and companionship is something which dominates peoples' lives in societies everywhere. Given the strength of human beings' illusions, their hopes and their biological drives, it would not be easy, later on, for the Buddha to point out the futility of the time and energy spent in this quest, and its high price. There would be more chance of his audience heeding someone who, as was his case, had married and satisfied three of the most beautiful brides in the land and who had enjoyed the company of the many young consorts in his royal harem. Of these, the beautiful Yasodhara, a princess in her own right, was his main bride and the mother to his only official child, Rahula.

![]()

Sixth Deed: Renunciation of Samsara, Leaving his life as a Prince

The royal palace where the Buddha stayed was enclosed with high walls and four gates facing each of the cardinal points. The Buddha went for a walk outside of the precincts of the palace, each time leaving through one of the different gates, and each time he saw something that gave him a different lesson on life.

The first time he went out through the eastern gate of the palace and saw the suffering of an old man, discovering for the first time that all persons experience the degeneration of the body. Another time he left the palace through the southern gate and saw a sick person and discovered the suffering that all persons at one time or another suffer. The next time he went out through the western gate and saw a dead person and discovered the pain of death which all persons must undergo. This hit him hard because he realized that no matter how rich you are, no matter how powerful you are, no matter how much pleasure and enjoyment you have, there is nothing you can do to run away from the suffering of old age, sickness, and death. He realized that there was no way to avoid these; even a king could not buy his way out of this suffering. No one can run away and hide from this suffering. No one can fight and defeat these three kinds of suffering.

But then the Buddha realized that maybe there is a way out: the practice of a spiritual path. The Buddha understood this when he left the palace through the northern gate and saw a begging monk. That moment he felt great weariness with the world and renounced the world at the age of 29. He left his worldly royal life in search of the truth.

The details of his fourfold vision of ageing, sickness, death and a holy man, and the story of the feast on his last day at the palace, when Rahula was born, are poignant indeed and told in many of his life stories. The common version of the renunciation is that he had his servant, whom he had sworn to secrecy, bring him his horse, Katanka, late that same evening. Cutting off his long hair—the symbol of his royalty—with his own sword, he rode off into the jungle to follow the religious life. The Mahayana version is that the Buddhas of the past, present and future emanated, gave him the vows of monastic ordination, his robes and hair-cutting, and that he set off on the eternal way of the monk. To teach others renunciation, he had himself to show the courage and ability to leave behind all the wonders and joys of his temporal life, in order to seek timeless wisdom.

![]()

Seventh Deed: Practice of Austerities and Asceticism, and then Renouncing them

After the Buddha left home, he led a life of austerities for six years by the banks of the Nirajana river in India. These austerities did not lead to his enlightenment, but the years spent doing ascetic practices were not wasted because they had the specific purpose of showing future disciples that the Buddha had put a very great amount of effort, perseverance and diligence into achieving the goal of enlightenment. By doing this, the Buddha demonstrated that as long as someone is attached to money, food, clothes, and all the pleasures of life, full dedication to spiritual practice is impossible. But if one gives up attachment, then the achievement of Buddhahood becomes a possibility. So that is why the Buddha engaged in this deed of six years of austerities by a riverside.

In the end, the Buddha gave up the practice of austerities, by accepting a bowl of yogurt. In contrast to the austerities, the Buddha ate this nutritious food and gave his body a rest (regaining all his physical splendour and health). He put his clothes back on and went to the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya. The Buddha gave up the austerities to show his future followers that the main object of Buddhist practice is working with one’s mind. We have to eliminate the negativity in our mind and have to develop the positive qualities of knowledge and understanding. This is far more important than what goes on outside of us. So, austerities are not the point in themselves, they alone do not bring us enlightenment.

For six years, much of it spent in the company of five other ascetics, he practised meditation and asceticism. He trained under the finest meditation teachers of his day, but soon exhausted what they had to teach him. He then devoted himself to austerities. He ate less, endured the burning sun more and practised hardships more stringently than anyone had ever done. Much of this occurred in the area of the river Neranjara. Often, he meditated for many days, without eating or moving, beneath the tall trees on its banks, with a rock for a cushion. At the end, he was such a skeletal bag of bones that his spine could be seen protruding through the skin of his abdomen. His brilliant aura and special marks had disappeared. This severe self-denial would not only serve as a proper basis for dismissing asceticism as the main way to truth, but would also demonstrate his own mastery of diligence and show his teaching to be not just an intellectual conclusion but the fruit of powerful personal experience. His ascetic period ended with him receiving the offering of a special bowl of rice gruel. Someone who had made a deep commitment to Sakyamuni, in a previous life when he was a Bodhisattva, was reborn as a young milkmaid. She fed ten of her best cows with the milk of a hundred cows. Then she milked the ten cows and fed that milk to the best cow of all. Its milk she mixed with honey and the finest rice. Taking this in a golden bowl, she approached Sakyamuni and offered it to him. As he drank it, his special marks and halo returned in an instant and he casted the bowl into the river saying, "If I am to find enlightenment, may this bowl float upstream." It did.

![]()

Eighth Deed: Taking His place at the Vajrasana in Bodh Gaya, the seat under the Bodhi Tree

After giving up the ascetic practice, the Buddha went to the Bodhi tree and vowed to stay under this tree until he reached final awakening.

By doing so, the Buddha demonstrated to us that true practice should be in the middle of the two extremes: practicing too many austerities and being too indulgent. The first extreme is when you starve yourself or you don’t allow yourself food and drink. These practices also involve placing yourself in extreme physical conditions such as being too hot or too cold. This is pointless because it has no true significance. The other extreme is when you just follow any of your desires. This is endless because there is a constant escalation in your desires. If you have ten pleasures, you’ll want a hundred. If you have a hundred, you’ll want a thousand; so you will never find any satisfaction and you will also never be able to practice the Dharma either. So the Buddha wanted to show us that we have to avoid the extreme of too much austerity and too much indulgence: true practice lies somewhere in the middle.

He then set out for Vajrasana, the place we now call Bodh Gaya. It is said to be the spiritual ‘centre of gravity' of this world and the place where each of the 1,002 Buddhas will manifest enlightenment. On the way there, he met another person with a special dharma connection: a young man who offered him a bundle of kusha grass as a meditation cushion. Arriving beneath the great tree, a ficus religiosus, he arranged the grass and sat in meditation.

![]()

Ninth Deed: Victory over of the leader of Maras, Papiyan

When the Buddha was sitting under the Bodhi tree, Papiyan, the leader of Maras, used forms related to the three disturbing emotions (sometimes called kleshas) of ignorance, desire, and aggression to try to lure the Buddha away from his pursuit of enlightenment. The first deception, representing ignorance, was that the Buddha was asked to abandon his meditation and return immediately to the kingdom because his father King Shuddhodana had died and the evil Devadatta had taken over the kingdom. This did not disturb the Buddha’s meditation. Then Papiyan tried to create an obstacle using desire; his beautiful daughters tried to deceive and seduce the Buddha. When this did not disturb the Buddha’s meditation, Mara then used hatred by coming towards the Buddha surrounded by millions of horribly frightening warriors who were throwing weapons at the Buddha’s body. But the Buddha wasn’t distracted or fooled by these three poisons. He remained immersed in compassion and loving-kindness and therefore triumphed over this display of the three poisons and was able to eventually achieve enlightenment. This deed of the Buddha is represented by the image of the Buddha "taking the earth as witness," gently touching the ground with his right hand and holding a begging bowl in his left hand. The Buddha wasn't tricked by Mara's deceptions, and also miraculously proved to Mara that for eons he performed innumerable good deeds by having the earth itself testify.

From an absolute point of view, Sakyamuni was already completely purified and realised. He had already become the perfection of dharmakaya. But to instil, on a relative level, an understanding of the need to attain total virtue and wisdom, he needed to show attainment of this utter purity. Having taken up his seat under the Bodhi tree, he entered into the absorption in dharmakaya known as the ‘vajra-like samadhi'. With his manifestation of enlightenment imminent, the hosts of negative energies and beings of this world came to distract him. They produced phantasms of sensuality, hordes of frightening demon armies and other illusions, in a vain attempt to hinder his achievement. By his remaining unperturbed in the natural loving compassion and emptiness of the vajra-like samadhi, the hosts of negative forces (mara) were defeated. The weapons they threw turned into flowers, adorning the Buddha's presence. It is said, in certain scriptures, that these evil entities were unable to affect India for many centuries following this: it seemed to them as though it were protected by a great wall of impenetrable fire. Thus the golden age of enlightened teachings could establish itself. The outer ‘evil forces' are the external mirror image of the internal ones. One could also consider the Buddha's total enlightenment as being the final elimination of every trace of the ‘four evils' (four maras): those of death, the defilements, the aggregates and pride.

![]()

Tenth Deed: Attainment of Enlightenment reached while meditating under the Bodhi tree

Since the Buddha developed all the qualities of meditation to the utmost stages, he was able to reach enlightenment. He did this to demonstrate that we also can reach enlightenment. As a matter of fact, one of the main points of the whole Buddhist philosophy is to show us that Buddhahood is not something to be found outside of us, but something we can achieve by looking inside ourselves. In the same way as the Buddha Sakyamuni reached enlightenment, we also can achieve enlightenment. And the qualities that we will attain with enlightenment will be no different from the ones the Buddha attained. Also, the Buddha managed to eliminate all the negative emotions, the same ones we presently experience.

At dawn the next morning, the day of the full moon in the Vaishakha month, he manifested total enlightenment. He was thirty-five. After three cosmic aeons of association with this world, he at last appeared in it as a fully purified being, a flawless expression of the absolute truth and the presence of omniscience.

![]()

Eleventh Deed: Teaching the Dharma

The Buddha turned the Wheel of the Dharma three times, meaning He taught in three different ways. The first is called the Hinayana, which consists of the teachings on the Four Noble Truths, meditation and developing an understanding of the emptiness of self. The second is the Mahayana teachings which involve the study of emptiness of phenomena and practicing the Bodhisattva path. The third turning is the Vajrayana which involves the understanding that everything is not completely empty, but there is also Buddha-nature that pervades all sentient beings. When the Buddha lived in India, the population of India believed that if one made offerings and prayed to a god, then that god would be satisfied and happy. In turn that god would grant liberation and happiness. They also believed that if one didn’t make offerings and pray to the god, he would be very angry, throwing you down to the hells and inflicting other states of suffering upon you. This idea of a god isn’t really one of a special deity, it is only the embodiment of desire and aggression. In Buddhism, we do not expect our happiness or our suffering to come from the Buddha. It is not believed that if we please the Buddha, he will bring us happiness and if we displease the Buddha, he will throw us into samsara or some lower realm. This may seem to be a contradiction that Buddhists don’t believe in supplicating a god. Buddhists believe that there are gods, there are deities, which were created by mind. But unlike theistic religions, Buddhists do not believe these deities created the universe. These deities cannot affect your individual karma by rewarding and punishing you. So, the possibility of happiness or reaching liberation is entirely up to us. If we practice the path that leads to liberation, we will attain Buddhahood. But if we do not practice it, then we cannot expect to reach enlightenment. The choice is entirely ours. It’s in our hands whether we want to find happiness or suffering. But still there is something that comes from the Buddha and this is the path to liberation. To provide us with that means for liberation, the Buddha turned the Wheel of the Dharma.

He did not start teaching the Buddha Dharma immediately but remained in silence for seven weeks, in order to show the profundity of what he had realised and to give the Devas of the planet the chance to gather virtue by requesting him to teach. They eventually came to him, prostrated and supplicated him to turn the wheel of universal truth for the welfare of beings on Earth. After these seven weeks Brahma presented the Buddha with a beautiful conch shell, the spirals of which all turned to the right. This shell was so beautiful and like no other shell in this world. Indra gave him a 1000-spokes Dharma wheel. In the deer forests near Benares and other places, he taught the Four Truths and 84,000 dharmas common to all Buddhism. At the Vulture Peak and other lesser-known places, he taught the special path of Mahayana. To King Indrabhuti and others, he taught the secret teachings of Vajrayana. Over a forty-five year period, and through the three turnings of the Wheel of Dharma, he transmitted all that needed to be known: the profound path to peace and everlasting happiness.

![]()

Twelfth Deed: Passing into Parinirvana at the age of 83 in the town of Kushingara

The Buddha asked his students if they had any final questions and then lying on his side, in the lion’s posture, he passed into Parinirvana.

His last words were, “Bhikshus, never forget: Decay is inherent in all composite things. Therefore, work diligently.”

Throughout all this time, the Buddha had been an expression of dharmakaya, which is beyond any coming or going. Yet, in order to instil diligence and a sense of urgency in his disciples, and in order to dispel the wrong notions of his having eternal, concrete divinity or the wrong notions of nihilism, he passed into Parinirvana. If even the physical presence of Buddha must seem to die, how much more so the likes of ordinary beings! His passing also highlighted the need for all Buddhists to assume personal responsibility for their own welfare, and not to be over-dependent upon the spiritual radiance of others. Buddha Sakyamuni's life, chosen here to exemplify the meaning of the term ‘supreme nirmanakaya', is not unique. The twelve deeds are typical of the activity of such supreme nirmanakaya throughout the universe. Whenever worlds are ready to receive them, those already enlightened in sublime spheres demonstrate these twelve deeds, which establish the universal truths of Dharma in the very best and most lasting way. It is the supreme dialogue between truth and ignorance, between the pure and the impure, that will continue for as long as worlds exist.

Note:

The Twelve Deeds of the Buddha prayer is commonly recited at Stupas, and in general to consecrate a new assembly hall or just a large Sangha gathering.

The prayer itself gathers enormous blessings.

It is available at TNG-Shop under the reference "TNG-GS 019-E Thub Töd".

It is highly recommended and practiced by the ordained community to commit this text to memory.